In the quiet hours before dawn, Mona McGuire was jolted awake by a loud pounding on her barracks door. Her heart raced as detectives from the Army’s criminal investigation division barged in. Stripping her bedding, handcuffing her, and taking her along with three other female soldiers to headquarters, their intent was clear. They fingerprinted her, snapped a mug shot, and subjected her to hours of intense questioning.

This was May 1988, and McGuire’s interrogators seemed to know everything about her, including her romantic relationships and even the specifics of her menstrual cycle. Under mounting pressure, she admitted to having been intimate with women. That confession derailed her Army career at the age of 20, branding her with archaic charges of sodomy and indecent acts to avoid a court-martial and possible imprisonment.

“I was embarrassed. I was ashamed,” McGuire, who now lives in suburban Milwaukee, reflects. For 35 years, she kept the true reason for her discharge a secret, revealing it only to her closest friends. Yet, for the Department of Veterans Affairs, even today, she remains an outcast, ineligible for benefits like healthcare due to an outdated, discriminatory policy.

McGuire is among as many as 100,000 veterans forced out of the military because of their sexual orientation from the 1950s until the repeal of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in 2011. While new reforms may provide relief for many, those like McGuire, with criminal convictions for being gay, still bear the stigma.

Baby steps for vets with ‘bad paper’

Until 1993, the military strictly prohibited gay and lesbian individuals from serving. “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” introduced during the Clinton administration, allowed LGBTQ people to serve as long as they kept their sexual orientation hidden. Despite this, countless officers and enlisted personnel were discharged, often unfairly accused of misconduct. The repeal of the policy in 2010 under President Barack Obama aimed to rectify this discrimination.

Since then, both the Defense and Veterans Affairs departments have made strides in addressing past injustices. However, “less than honorable discharges” due to sexual orientation are not automatically erased. As of June 25, the VA began considering appeals from veterans with “bad paper” who can prove that compelling circumstances like harassment or discrimination led to their discharge. Despite these changes, the shifts remain limited and don’t help veterans like McGuire, who were court-martialed or accepted discharges “in lieu of court-martial.”

A federal lawsuit last summer sought to upgrade discharges for those discriminated against due to their sexual orientation. In response, the Pentagon promised to review records of veterans discharged under “don’t ask, don’t tell,” yet there’s still no update or timeline.

The gravity of this injustice is starkly illustrated by a Vietnam War veteran’s gravestone that reads: “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

Worried ‘someone would tell on us’

The inequality LGBTQ service members faced was pervasive. Commanding officers had the discretion to either discreetly discharge a soldier with an honorable discharge or, as in McGuire’s case, make a public example of them. McGuire, who enlisted in the Army in 1987 to honor her late father’s legacy, found her fit in the rigorous and disciplined environment of the military police.

There, she met Karla Lehmann, a fellow soldier, and they quickly grew close. Living in constant fear of being outed, their secret relationship came to a halt one morning in May 1988 when they were dragged from their barracks and interrogated. Threatened with court-martial and imprisonment, they eventually confessed.

More than three decades later, with societal changes and a more accepting environment, McGuire hoped to clear her military record. In 2022, she applied for a discharge upgrade, detailing her post-service struggles and the honorable life she built with her wife of over 30 years.

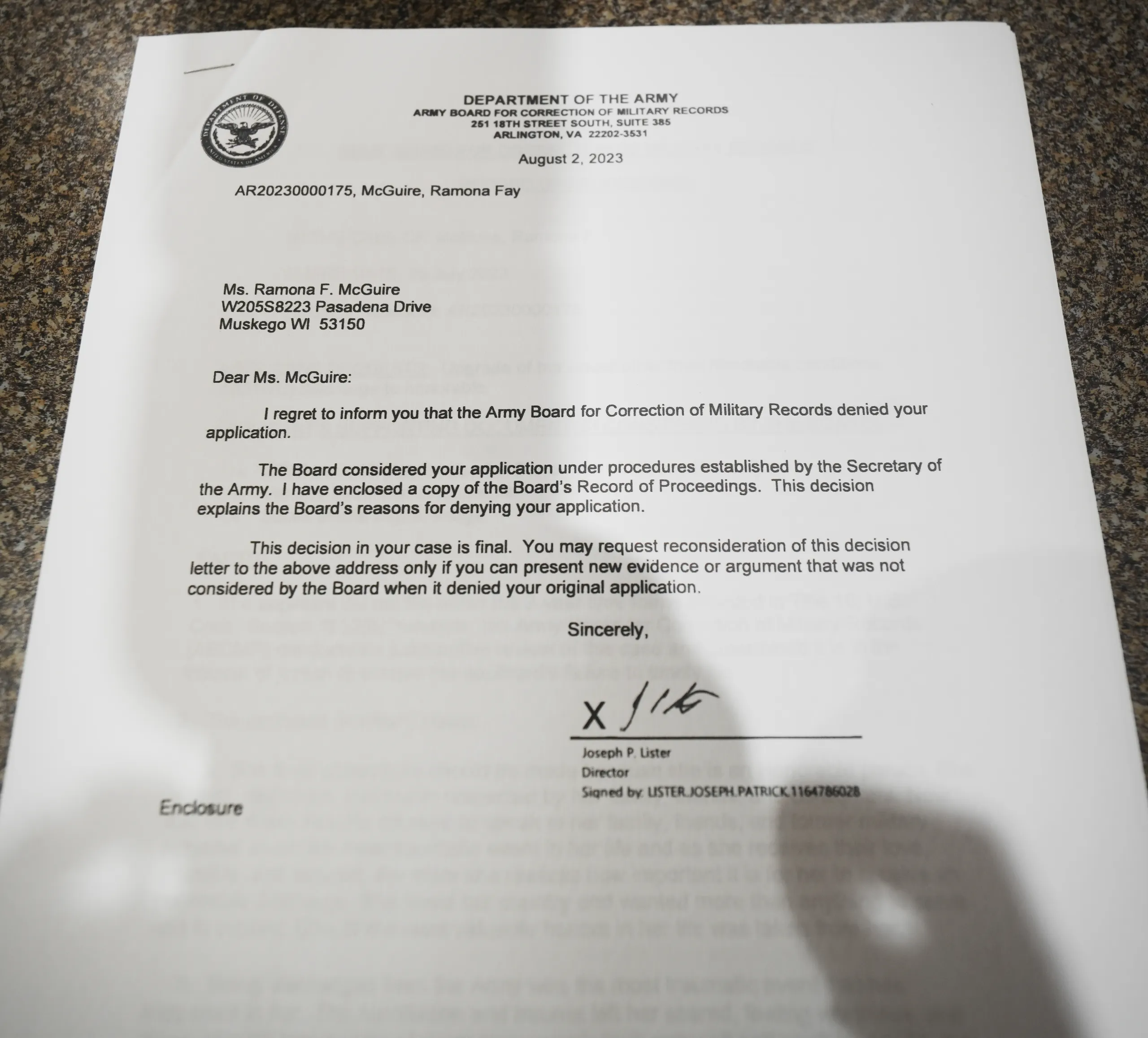

‘I regret to inform you …’

Despite following guidelines for granting upgrades to discharges based solely on anti-LGBTQ policy, her application was denied in August 2023. The eight-page denial highlighted her admission of guilt and her “failure” to provide compelling evidence of post-discharge depression.

Christie Bhageloe, an attorney helping McGuire with her appeal, finds the denial perplexing. “Her charges were solely for being gay,” says Bhageloe. “This should not require legal assistance.”

VA benefits to keep troops in line

The new VA rules, supposed to be more lenient, still face resistance. The Department of Defense argues that access to VA benefits must have strict barriers to maintain military order. Advocates argue that this stance undermines the VA’s mission to care for veterans.

In a statement, VA spokesperson Gary Kunich emphasized the ongoing efforts to address issues LGBTQ veterans face but acknowledged that those discharged “in lieu of court-martial” could still encounter barriers.

For McGuire, the journey towards justice continues. Her attorney requests a discharge upgrade and a retroactive extension of her service time, seeking eligibility for VA benefits.

The bombshell Facebook message

In January 2018, McGuire and her friends learned who had informed on them—all those years ago. The confession came via a Facebook message from one of their former platoon members, regretting her actions. While Lehmann expresses a level of acceptance, McGuire remains hurt and angry.

Despite these challenges, McGuire dreams of reenlisting, feeling joy imagining herself back in uniform, reliving memories before that fateful morning in May.

If you or someone you know is a veteran who faced similar discrimination, please consider sharing your story. Let’s work together to right these wrongs and honor the service of all veterans.